Progress Report - February 2022

The big news is that we have finally ‘broken ground’ and started digging the foundations. We had to wait until we were ready to submit our plans to South and Vale in order to get building control permission. They have posed a few questions, which we are busy answering, but they are happy for us to start construction.

You will see from the photos that the hole is now very deep – it has to accommodate the ground strengthening blanket of aggregate and all the steel we showed you in the last report. Also, the foundations are set a little low so we can fit floorboards over the concrete raft – it is important that you hear footsteps as you walk around the station building, as you would have originally, rather than the sterile feel you get from a concrete floor. The void is also useful for running heating pipes and cables below the floor.

The sheets of plywood you can see are simply protecting the base from soil that is likely to be displaced by the big ride-on vibrating roller we have hired in to tamp in the type 1 aggregate base.

Mechanical help is essential. As befitting a preservation establishment, our plant is rather old. You will see our vintage 50-year-old JCB has been put to good use by our Tuesday gang. Both our slightly newer (but not by much) dumper trucks have been busy transporting the spoil away into the land just acquired adjacent to the branch line. We’ve suffered from a few broken hydraulic pipes, but they are quickly repaired by Dave. It’s not just steam engines that need constant maintenance, but at least with this kind of plant you can easily get hold of spares. When we bought locomotive Burton Agnes Hall, it was only 17 years old, so perhaps we should celebrate our working vintage plant as exhibits!

It might be argued that building properly began on Tuesday February 22 when the first layer of geotex and some 30 tons of type 1 were placed in the hole, thereby commencing construction of the foundations.

The ‘state of the hole’ on 24-Feb-22 with the first layer of type 1 almost complete.

Last week three of us were assigned for a day of road mending, as this kind of plant does damage footpaths, and we are open again for half-term visitors. But the rain on Tuesday meant other areas have been churned up a bit. We’ll do some more repairs when the ground dries up again.

Most of the work of the Thursday gang recently has been in repairing and replacing fences in the vicinity of the works, as the wooden posts have rotted away after 40 or more years in the ground. We are pleased to be building proper post and wire fencing that is the GWR height of 4’ 10”. The previous fence used split telegraph poles and never looked quite right, but the new one has the proper posts, with points on the top and the correct number of wires.

In fact, the area is turning into a veritable museum of fencing around railways. For that reason, we have written a bonus section on GWR fencing. It is only slightly more interesting than it sounds, but it is important that we create an authentic railway setting by getting things like this right.

We have, in recent weeks, been thinking about the canopy, and in particular the fine brackets (sometimes described as spandrels) and the distinctive lion’s head castings. Alan Price has arranged for a foundry to cast some replica lion’s heads in aluminium, one of which will be placed on the end of a canopy bracket he restored that we have erected behind the new fence by the information board. We would be very interested to hear from anyone wishing to sponsor the manufacture of the new spandrels, or any other element of the building.

So, by the next update, we hope to have completed the ground strengthening and be preparing the cages of reinforcement. Also, we should have finished the fencing.

If you wish to join the volunteer team, contact Tim Part via the DRC office or by sending an e mail to gws.heyford@outlook.com.

Great Western Fencing – a beginner’s guide

To start with we must understand the purpose of railway fencing. Originally this served only two purposes. to stop livestock straying on the line and to stop trespass from the railway onto adjoining land. This was made a legal requirement in the early days of railways by the Railways’ Clauses Act of 1845 which introduced a requirement for: “… sufficient posts rails, hedges, ditches, mounds or other fences for separating the land taken for the use of the railway from the adjoining lands not taken and protecting such lands from trespassing, or the cattle of the owners or occupiers thereof from straying thereont …”.

It was not until 1972 that a legal judgement in the House of Lords (British Railways Board v Herrington [1972] AC 877) found that railways, and indeed other landowners were required, to protect trespassers from the hazards presented by any 'dangerous infrastructure' on their land. This requirement being later enshrined in the 'Railway Safety (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act' of 1993.

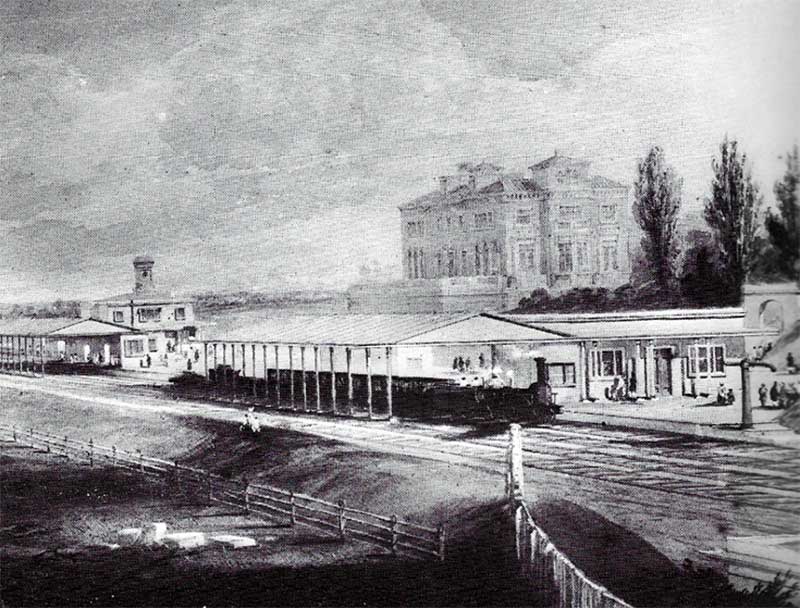

Our early picture of Heyford Station shows a very simple post and single rail fence. Whilst this was prototypical, we haven’t adopted it as we need to keep children from wandering underneath it and keep them from danger.

Fencing on Heyford station approach. Note that this does not protect a boundary between the public and the tracks

The engraving below, of Slough station, demonstrates that early boundary fencing was often the same as that found on farms. A common type was chestnut ‘cleft fencing’ where coppiced wood was split to make posts and rails. We have installed some around the copse next to the Broad Gauge track and in front of the canopy spandrel we have just restored.

New cleft chestnut fencing around the ‘Broad Gauge Copse’

The technology allowing wire to be made cheaply probably post-dates our station by a few years, but soon it was the normal way to mark the boundary. It keeps livestock out, and is difficult to ignore. The Great Western used it extensively – note how the spacing of wires is more concentrated at the bottom where children or pets might otherwise climb through. Our posts are cut from old sleepers and it is probable that the GWR did the same. Originally a braced post would keep the wires strained – ours are also made from old crossing timbers – slightly more substantial than a normal sleeper and similar to baulk road (Broad Gauge in-line) sleepers. When the Broad Gauge ended, the GWR began to use the old ‘bridge rail’ for terminal and straining fence posts [and for anything else that needed a substantial rail, such as to strengthen bridges or to hang a cast iron sign on, or to support the porch on Frome Mineral Junction Signal Cabin.] You will see several terminal and straining posts plus some intermediate posts made of bridge rail in the area. Note how the wire is kept taut by using adjustable eye bolts, that can be tightened as the wire stretches over time.

Steve Ryder and Robert Heron with a newly completed section of sawn sleeper and wire fence

Sometimes the GWR made a wooden post and multiple rail fence, and naturally we have an example of this as well. It was commonly used to demarcate paths and at cattle loading banks. Note how intermediate posts are smaller. We will be putting more of this up between the proposed Station Gate and the entrance to the station forecourt.

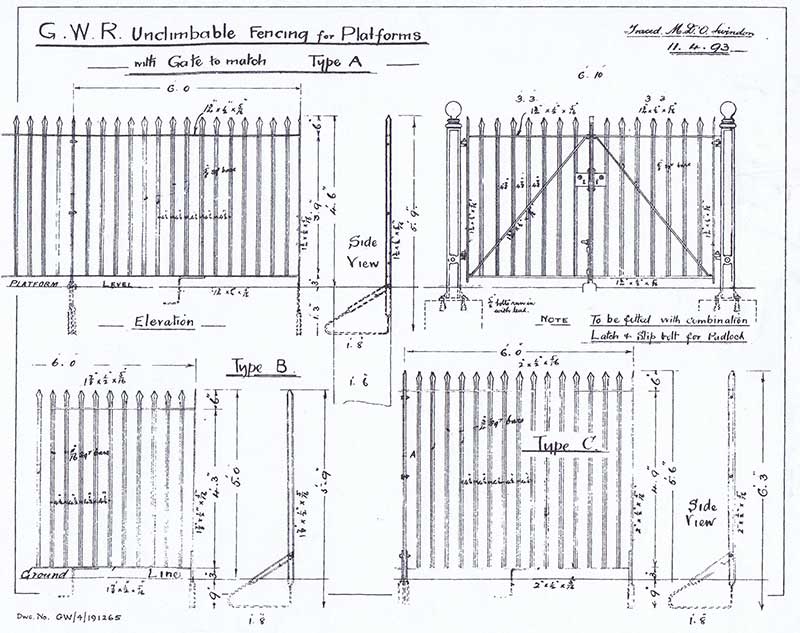

In the Edwardian era, the GWR realised they needed something more substantial to keep fare dodgers off the platform and thieves from their goods yards and docks, and the public away from dangerous places, so they erected many miles of ‘unclimbable’ wrought iron spear fencing. Around stations it is 4’ 6” high, so is probably not unclimbable, but if you get it wrong trying to climb over it, it would be very uncomfortable. In some industrial locations it was 6’ high. Until recently it was very common on the modern railway [and Network Rail has produced ‘new’ spear fencing for some stations] but often it is replaced with palisade fencing that only the very determined can climb over. You can see spear fencing at the back of the Oxford Road station platform and around Didcot Halt and also in front of the Transfer Shed. Note that away from station areas it is painted with bitumen rather than paint.

We received some redundant spear fencing panels last year courtesy of Transport for London who were upgrading fencing at Taplow, so we will be able to fence the station forecourt with it. They also gave us some gates and gate posts. The cast iron gate posts are a thing of beauty, and come in two designs – square with a ball on top and octagonal. Both can be found around the Railway Centre.

Provincial passenger stations often also had wooden picket fencing. You can see this to the right of the historic picture of the station here and also at Didcot Halt. The GWR did not normally use anything more than post and wire fencing at Halts, but Didcot Halt is a very busy station. Picket fencing needs a lot of maintenance, but labour was cheap then.

Heyford Station. Reproduced from: Brunel: A Railtour of his achievements published by Middleton Press (01730 813169, www.middletonpress.co.uk)

In the 1930s, the GWR began to use concrete fence posts rather than wooden fence posts. Wooden fence posts do need to be replaced regularly. We have some concrete posts around the copse, situated further along the demonstration line. We will be re-wiring some of that presently, too! When you look out of the window on the modern railway, you will often see fencing like this still in use in rural areas – it may be concrete, but it may be 80 years old and still doing its job, possibly with the original galvanised wire.

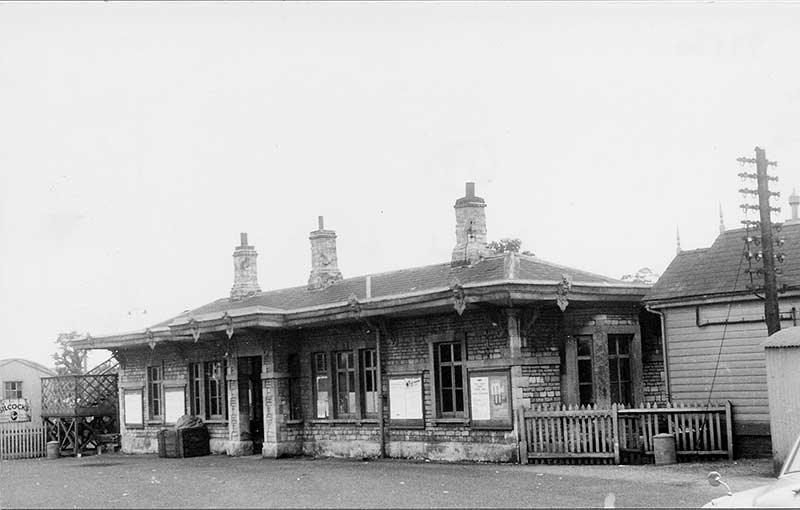

Heyford Station 1986. Photo: Dave Longman

Of course, the railway also made use of hedges and even stone walls – there is a stone wall at the back of the ‘up’ platform at Heyford itself – the platform opposite where our station building once stood. Maybe one day we will build a stone wall somewhere!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article, that is intended to show that the Society cares about getting the detail right.